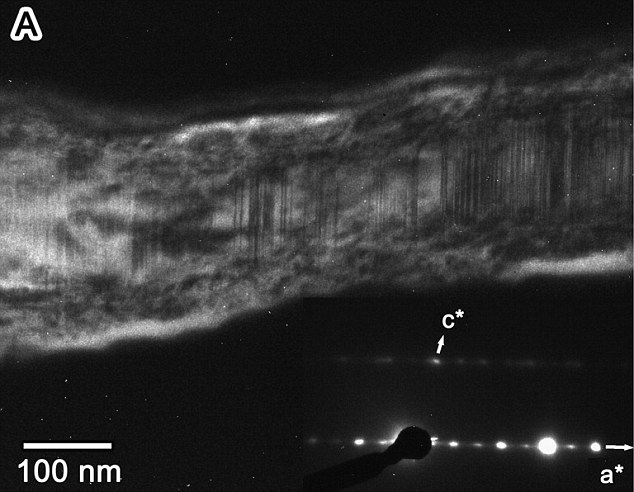

Chondritic porous interplanetary dust particles (CP IDPs) collected in the stratosphere are regarded as possibly being cometary dust, and are therefore the most primitive solar system material that is currently available for analysis in laboratories. In this paper we report the discovery of more than 40 chondritic porous micrometeorites (CP MMs) in the surface snow and blue ice of Antarctica, which are indistinguishable from CP IDPs. The CP MMs are botryoidal aggregates, composed mainly of sub-micrometer-sized constituents. They contain two components that characterize them as CP IDPs: enstatite whiskers and GEMS (glass with embedded metal and sulfides). Enstatite whiskers appear as <2-μm-long acicular objects that are attached on, or protrude from the surface, and when included in the interior of the CP MMs are composed of a unit-cell scale mixture of clino- and ortho-enstatite, and elongated along the [100] direction. GEMS appear as 100–500 nm spheroidal objects containing <50 nm Fe–Ni metal and Fe sulfide. The CP MMs also contain low-iron–manganese-enriched (LIME) and low-iron–chromium-enriched (LICE) ferromagnesian silicates, kosmochlor (NaCrSi2O6)-rich high-Ca pyroxene, roedderite (K, Na)2Mg5Si12O30, and carbonaceous nanoglobules. These components have previously been discovered in primitive solar system materials such as the CP IDPs, matrices of primitive chondrites, phyllosilicate-rich MMs, ultracarbonaceous MMs, and cometary particles recovered from the 81P/Wild 2 comet. The most outstanding feature of these CP MMs is the presence of kosmochlor-rich high-Ca pyroxene and roedderite, which suggest that they have building blocks in common with CP IDPs and cometary dust particles and therefore suggest a possible cometary origin of both CP MMs and CP IDPs. It is therefore considered that CP MMs are CP IDPs that have fallen to Earth and have survived the terrestrial environment.

Recuperare polvere cometaria non è semplice: la missione della NASA Stardust aveva incontrato la cometa Wild 2 nel 2004, rispedendo il suo prezioso carico a Terra con una capsula atterrata nel 2006; la missione dell'ESA Rosetta ha dovuto viaggiare 10 anni per raggiungere, seguire ed analizzare il suo target, la cometa 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Gli scienziati hanno anche provato a catturare alcune particelle direttamente dall'alta atmosfera terrestre tramite un foglio "appiccicoso", che comunque contamina i campioni insieme alle altre sostanze utilizzate per rimuoverli.

Questa volta, però, il team ha cercato sotto 58 metri di neve e ghiaccio antartico, in un luogo chiamato Tottuki Point.

Quando il ghiaccio si è sciolto in laboratorio, i ricercatori hanno scoperto al suo interno anche particelle di polvere estremamente piccole (tra i 10 e i 60 micrometri) che credevano inizialmente appartenenti ad un meteorite. Altre analisi, però, mostrarono che si trattava di condrite porosa interplanetaria (piccole particelle di materia che, assieme ai gas, è contenuto nel mezzo interstellare, lo spazio tra le stelle all'interno delle galassie), molto simili alle particelle di cometa raccolte da Stardust e a quelle catturate nell'atmosfera terrestre.

Già nel 2010 una squadra francese aveva trovato delle particelle ipotizzando che fossero di origine cometaria ma questa è la prima ricerca che ne conferma il ritrovamento. Per di più gli scienziati hanno sempre ritenuto che polvere così piccola non riuscisse a sopravvivere attraverso la nostra atmosfera e poi, alle rigide condizioni ambientali. Ma questa grande scoperta permetterà di analizzare direttamente nuovi campioni per studiare l'evoluzione del nostro Sistema Solare e l'origine della vita sulla Terra.